🧪 Smart Pointers (distilled)

Background

Programming mostly in garbage-collected languages (java, python, etc.), there are a lot of things that I took for granted - if I even knew about them -. These things came to hunt me when trying none garbage-collected languages like C++, rust, etc (especially rust). Most of the issues are related to resource management and the main resource that causes problems is memory. To avoid such hassle there are patterns developed to safely and efficiently manage memory and other resources. Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII) is the pattern to perform just that, it was first introduced in C++ mainly through “smart pointers”, then rust came and adopted this pattern as part of the language.

Problem

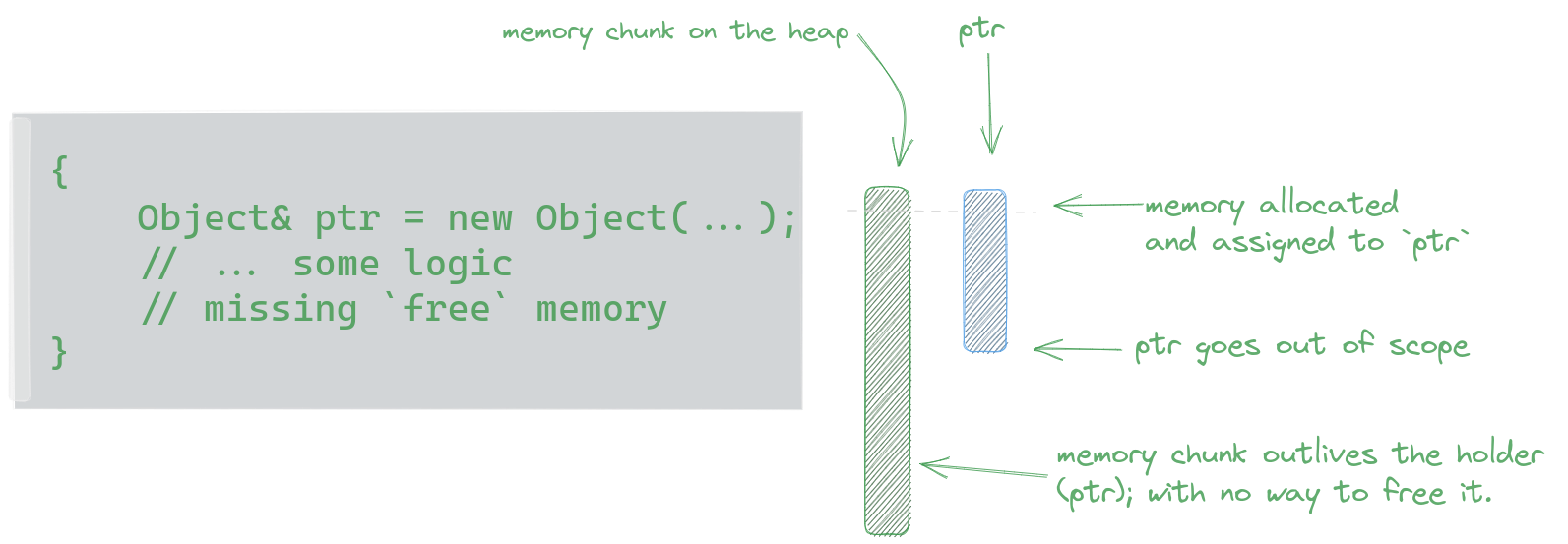

When developing an application that is supposed to be running for long periods (e.g. servers), managing different resources is a skill you have to master. Resources are - to some extent of correctness - anything of limited supply like (opened files, allocated memory, sockets, allocated memory, locks, allocated memory, etc.). If you miss even for a tiny bit, you risk leaking resources (holding on to resources that are not used and there is no way to free them), or even corrupting resources (giving the same resource to two different owners modifying it with no guarding mechanism). Studying all these kinds of problems, experts found patterns. These kinds of problems happen when the resource holder and the resource itself outlive each other. For example, memory leaks happen when the resource (memory) outlives the ptr pointing to it, meaning ptr goes out of scope before freeing/deleting it.

The other problem of corrupting resources happens when the resource holder outlives the resource itself; this problem is hard to visualize in a static image 😓. But let’s consider this case, you are having a resource holder x_holder for some resource x. Let’s say that this x_holder is shared across threads and one of the threads by mistake frees x through its shared x_holder - without knowing that there might be other threads using it -. At this point in time, there are all possible scenarios of bad undefined behavior, one of these scenarios could be that after the other thread frees x then the runtime - being the code that is supposed to manage the resource, not necessarily part of the developed application colud be the allocator when the resource is memory - assigned the same resource x to another part of the code to use it, but the very first thread is still have holder x_holder to that resource x meaning that this thread and the newest holder of the resource - apparently they don’t know of each other - will continue corrupting the state of each other 🫨.

RAII

So after seeing that the root of all these problems is that the resource holder and the resource itself could have different lifetimes - one can outlive the other. Naturally, the fix follows, we need to tighten these two lifetimes to each other making it impossible - or as hard as possible - to have a resource holder that points to a freed resource or a resource allocated with no resource holder. The RAII principle satisfies that. It stands for Resource Acquisition Is Initialization - simply put - you only acquire a resource by initializing some object and the resource will be freed automatically when this object dies. In the following sections, we will take a look at two smart pointers that deploy the RAII principles: unique_pointer, and shared_pointer.

To see the benefits of using such pointers, I will present an oversimplified running example to get a good grasp of how these pointers enforce the RAII principles. The following is a simple struct containing an integer and prints to the standard output whenever an instance is created or deleted.

struct Object {

public:

int _a;

Object(int a): _a(a) {

std::cout << "created" << a << std::endl;

}

~Object(){

std::cout << "dead " << _a << std::endl;

}

}

unique_ptr

the simplest way to create an Object ptr is to use the new function and after that use the pointer and pass it around, the following example shows that:

int main() {

Object* ptr = new Object(1);

std::cout << "ptr -> " << (ptr->_a) << std::endl;

// oops

}

if we ran the previous snippet of code, we shall get

created 1

ptr -> 1

You probably noticed that we are missing the deallocation part, the destructor is never called. when using such manually managed memory languages you should take the burden of following all the execution paths and make sure that the allocated memory is freed/deleted at the end of each and every execution path - that also applies in cases where exceptions may fire. This two-line code as simple as it is represents the general case of memory leaks, and as we pointed, there should be delete ptr at the end of the function.

Here comes smart pointers for the rescue especially the unique_ptr. This pointer - as its name implies - ensures that there is exactly one owner of the memory. you might ask what is it good for? well, with this kind of semantics we - the authors of the smart pointers - can add some magic code within the smart pointers to automatically free/delete the memory to make the code safe against memory leaks, we can do that as the pointer owns the memory so it takes the responsibility to free it without the need for developers to remember to do that. we will see how they are able to do that in the following paragraphs. The next benefit of this pointer is that if you need to pass this pointer around, it isn’t copiable you will need to explicitly transfer the ownership of the pointer to the next owner using the std::move function. This also makes the code proof against memory corruption as there will never be a pointer to freed memory (dangling pointer), the following example - stuffed with printing - will show how unique_ptr works.

void other_func(unique_ptr<Object> ptr) {

std::cout << "ptr -> " << ptr-> a << std::endl;

}

int main() {

unique_ptr<Object> ptr = std::make_unique<Object>(2);

std::cout << "ptr -> " << ptr->_a << std::endl;

std::cout << "before other_func" << std::endl;

// other_func(ptr) will result in a compilation error, no copy constructor

other_func(std::move(ptr));

std::cout << "after other_func" << std::endl;

}

If we ran the previous code we shall get the following:

created 2

ptr -> 2

before other_func

ptr -> 2

dead 2

after other_func

Take your time tracing the code, but the important thing to notice here is that the object destructor is called before returning from the other_func call, but why?

The reason is very simple as we transferred the ownership of the memory to that function it takes the responsibility to free the resources when it is finished which is great. One more thing, the ptr in the main function becomes invalid after calling move because it no longer owns the memory so it shouldn’t be able access it.

shared_ptr

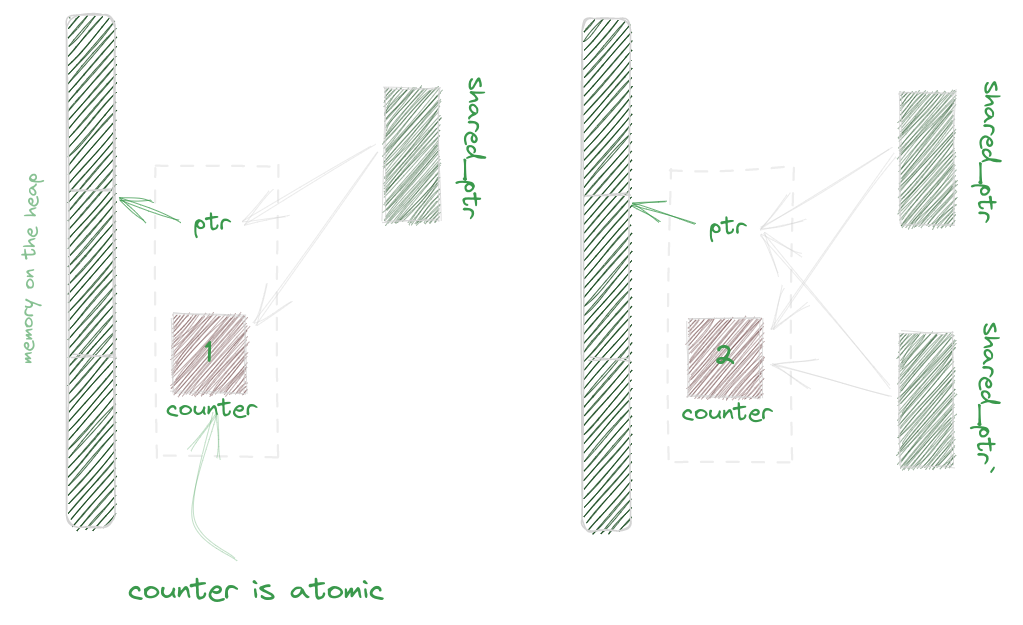

If you are new to the concept of ownership, you might now say: “what if I want to just share the pointer safely?” Here comes the next smart pointer shared_ptr to the scene. Shared pointers use reference counting to share and deallocate memory safely - much like how Python works effectively - it stores a counter of how many current owners of the underlying memory and only deallocates that memory whenever the counter reaches zero. The following example hopefully will show how this ptr works:

void other_func(shared_ptr<Object> ptr){

std::cout << "ptr -> " << ptr->a << std::endl;

}

int main(){

shared_ptr<Object> ptr = std::make_shared<Object>(3);

std::cout << "ptr -> " << ptr->_a << std::endl;

std::cout << "before other_func" << std::endl;

other_func(ptr);

std::cout << "after other_func" << std::endl;

}

If we ran that code, we shall get:

created 3

ptr -> 3

before other_func

ptr -> 3

after other_func

dead 3

Also, you should take your time tracing the code, but the important thing to notice here is that the destructor is only called at the end of the main function; at first, the reference counter is 1 and it got incremented when it’s copied other_func(ptr) so when the other_func is finished the counter was 2 and it decrements it to be 1 again without any other effect, then at the end of the main function the counter is decremented again reaching 0 so the smart pointer deallocates it by calling delete - which calles the destructor, as the reference counter implies that there aren’t any owners of this memory thus it’s not needed.

TL;DR

These pointers are also exception-safe. If any exception is thrown after declaring the pointer, the data will not be leaked and the pointer will handle it correctly - i.e. deallocating the memory in case of unique_ptr and decrementing the counter in case of shared_ptr. If anyone wonders how they are doing that, the essence of the mechanism is quite simple. You should notice that these pointers itself are allocated on the stack, whenever we exit a scope block (e.g. a function) there is a designated code that clears the stack frame.

Clearning that stack frame includes calling the destructor of said pointers, so they can delete the underlying data in their destructors or modified shared metadata that helps keep accessing such raw pointers valid (e.g. ref-counter in case of shared_ptr).

Here comes another simple example - yay 🎉 - showing the result of compiling the following function into assembly. Materializing the concept of stack frames - you might have encountered it in some computer organization course - you will see that the compiler adds two snippets of code at the begging and end of the function allocating memory for arguments and return variables and cleaning after the functions ends. The interesting part here is that you should notice a call to the destructor of the unique_ptr which we haven’t explicitly invoked.

void some_func() {

unique_ptr<Object> ptr = make_unique<Object>(1);

}

some_func():

;; INITING THE STACK FRAME

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 16

;;

;; function body

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

lea rax, [rbp-16]

lea rdx, [rbp-4]

mov rsi, rdx

mov rdi, rax

call std::make_unique

;;

;; CLEANING UP STACK FRAME

lea rax, [rbp-16]

mov rdi, rax

call std::unique_ptr::~unique_ptr() ;; NOTE: destructor is called automatically

leave

ret

;;

Establishing that the destructor will be called automatically regardless of how the execution of the function’s body goes, the features of the smart pointers could seem now reasonable and quite simple to achieve. In the case of the unique_pointer we know for sure that there will be no other part of the code that can have a valid pointer to the same chunk of memory so we can safely call delete _ptr to free the memory. In the case of shared_ptr - knowing that the destructor will be called - we can atomically decrement the reference counter, and whenever the counter reaches zero we can call safely delete the memory.